Forecasting "Dry Microburst" Potential From Soundings and Observations

Summer afternoons in the valleys of eastern California and western Nevada usually feature dry low level relative humidity. In certain cases where low levels are very dry (single digit relative humidities) and enough instability for showers and/or thunderstorms exists, there is the heightened possibility for severe (over 60 mph) outflow winds. Now, severe winds are possible from strong thunderstorms in many cases, even without very dry surface relative humidity. However, what makes very dry surface or low level conditions special is that severe outflow winds are possible even with weak convection such as light showers...or even just cumulus clouds! When severe winds are produced by convection with little or no rainfall reaching the ground, it is referred to as a "dry microburst". Microbursts can be of significant danger to aviation and, if they are strong enough, life and property.

Before we move onto what conditions we look for to determine the threat for dry microbursts, let's examine some of the features of general convective outflow winds. First, here is a diagram of the process and motions in a typical thunderstorm with precipitation:

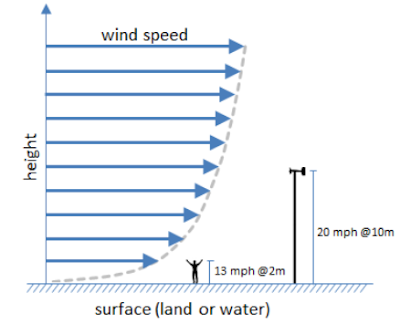

The yellow arrows in the diagram show the airflow involved in the the development and dissipation of a typical thunderstorm. Note the highlighted area in the dissipating stage image, which represents the outflow from a convective cell formed as precipitation and/or hail drags the surrounding air down with it as it falls towards the ground. This is known as "precipitation loading". Here is a more detailed diagram of outflow:

Finally, here is an excellent, very short conceptual video to show outflow movement, both simulated and with a wet downburst thunderstorm:

When the main forcing for outflow is from precipitation loading, it can be labeled as a "wet microburst" if the outflow is very strong or severe. However, if precipitation falling from a cloud does not reach the ground ("virga") due to sufficiently dry air below the cloud base, precipitation loading cannot explain severe outflow winds. In these cases, the mechanism for severe outflow winds is related to the evaporation (or in the case of ice crystals, sublimating) of the precipitation into the surrounding air, which cools it. This is called evaporational cooling. This concept is easy to experience if you have ever gone outside wet during a summer afternoon...the chill you feel is due to evaporation taking heat from the air around your body. Since cooler air is denser/heavier than warmer air, the pocket of evaporatively-cooled air below the cloud begins to accelerate towards the ground and will continue to do so until all the moisture is evaporated from the air. In extremely dry air with well-mixed atmospheric conditions, this acceleration can be quite profound...reaching in extreme cases over 100 mph! This is known as a "dry microburst".

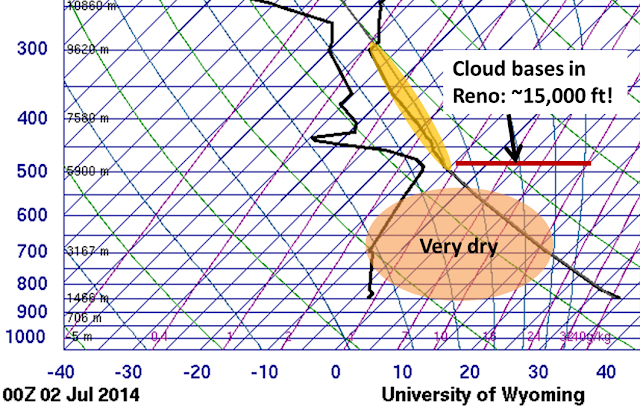

Now that we have explained the dry microburst concept we can venture into what forecasters look for to determine the threat for dry microbursts. Here is an observed Reno sounding from a dry microburst event in July, 2014:

At the time of this sounding, it was 95 degrees with 8% relative humidity at the National Weather Service office. Notice the very dry air (shaded pink) in place between the very high cloud bases (red line) and the surface...this is often referred to as an inverted-V sounding due to its appearance. Another crucial factor is the weak instability (yellow shaded area) in the atmosphere for the formation of convective clouds. Many times in summer eastern California and western Nevada will see inverted-V soundings due to very dry lower level air and strong heating/atmospheric mixing. However, there is often little or no instability aloft for the formation of convective clouds (cumulus or thunderstorms).

So, what happened on July 1, 2014? Here is an excerpt of events within a few miles of the NWS Reno office:

So, as you can see, wind gusts up to 71 mph and damage to trees and fences were reported in the Reno-Sparks area around 6 PM.

To conclude, microbursts can be of significant danger to aviation and, if they are strong enough, life and property. Meteorologists use a combination of soundings and surface observations along with model forecasts for convective development to determine the threat for dry microbursts. If you typically check out NWS Area Forecast Discussions, keep an eye out for mention of severe outflow winds on those very hot and dry summer days! Now, we will leave you with a short video of a dry microburst from our neighboring office in Elko, NV:

Before we move onto what conditions we look for to determine the threat for dry microbursts, let's examine some of the features of general convective outflow winds. First, here is a diagram of the process and motions in a typical thunderstorm with precipitation:

The yellow arrows in the diagram show the airflow involved in the the development and dissipation of a typical thunderstorm. Note the highlighted area in the dissipating stage image, which represents the outflow from a convective cell formed as precipitation and/or hail drags the surrounding air down with it as it falls towards the ground. This is known as "precipitation loading". Here is a more detailed diagram of outflow:

Finally, here is an excellent, very short conceptual video to show outflow movement, both simulated and with a wet downburst thunderstorm:

When the main forcing for outflow is from precipitation loading, it can be labeled as a "wet microburst" if the outflow is very strong or severe. However, if precipitation falling from a cloud does not reach the ground ("virga") due to sufficiently dry air below the cloud base, precipitation loading cannot explain severe outflow winds. In these cases, the mechanism for severe outflow winds is related to the evaporation (or in the case of ice crystals, sublimating) of the precipitation into the surrounding air, which cools it. This is called evaporational cooling. This concept is easy to experience if you have ever gone outside wet during a summer afternoon...the chill you feel is due to evaporation taking heat from the air around your body. Since cooler air is denser/heavier than warmer air, the pocket of evaporatively-cooled air below the cloud begins to accelerate towards the ground and will continue to do so until all the moisture is evaporated from the air. In extremely dry air with well-mixed atmospheric conditions, this acceleration can be quite profound...reaching in extreme cases over 100 mph! This is known as a "dry microburst".

Now that we have explained the dry microburst concept we can venture into what forecasters look for to determine the threat for dry microbursts. Here is an observed Reno sounding from a dry microburst event in July, 2014:

At the time of this sounding, it was 95 degrees with 8% relative humidity at the National Weather Service office. Notice the very dry air (shaded pink) in place between the very high cloud bases (red line) and the surface...this is often referred to as an inverted-V sounding due to its appearance. Another crucial factor is the weak instability (yellow shaded area) in the atmosphere for the formation of convective clouds. Many times in summer eastern California and western Nevada will see inverted-V soundings due to very dry lower level air and strong heating/atmospheric mixing. However, there is often little or no instability aloft for the formation of convective clouds (cumulus or thunderstorms).

So, what happened on July 1, 2014? Here is an excerpt of events within a few miles of the NWS Reno office:

So, as you can see, wind gusts up to 71 mph and damage to trees and fences were reported in the Reno-Sparks area around 6 PM.

To conclude, microbursts can be of significant danger to aviation and, if they are strong enough, life and property. Meteorologists use a combination of soundings and surface observations along with model forecasts for convective development to determine the threat for dry microbursts. If you typically check out NWS Area Forecast Discussions, keep an eye out for mention of severe outflow winds on those very hot and dry summer days! Now, we will leave you with a short video of a dry microburst from our neighboring office in Elko, NV: